In a year defined by deals — Disney-Fox, Discovery-Scripps, Sinclair-Tribune and AT&T’s government-interrupted merger with Time Warner — the biggest question for the media and entertainment sector entering 2018 is: Who’s next?

With six major movie studios shrinking to five and one of the Big Four broadcast networks suddenly on an uncertain path, it is clear that the M&A pace will only accelerate in the New Year. Among the dance partners likely to take a twirl: Viacom, CBS, Sony, Lionsgate and MGM. And that’s just on the content side — distributors, having taken 2017 off, are likely to tango in 2018, with Dish, Charter and Altice among the deal-inclined.

“In a consolidation phase like this, this is a game of musical chairs and the chairs are disappearing quickly,” said one industry executive.

This past year will go down as the time when traditional media companies had their collective Jurassic Park moment, looking in the rear-view mirror and seeing a giant T. Rex closing in. Consider the rankings of tech and media companies by total market capitalization — together, Apple, Google, Amazon and Facebook have a combined market cap that’s closing in on $3 trillion. The only traditional, non-telco media players at $100 billion or greater are Disney and Comcast. Viacom’s market cap is just $12 billion.

Media companies will likely feel pressure to bulk up, just to compete.

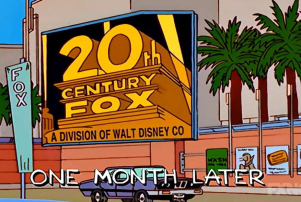

Disney’s $66 billion offer for the majority of 21st Century Fox’s film and television assets is widely seen as a defensive maneuver — an attempt to fortify the media conglomerate for battle with the bigger, better resourced technology companies that are rushing into the entertainment business.

In the coming clash of titans, Disney has expanded its pantheon of superheroes to include the X-Men, Fantastic Four and Deadpool, added a lucrative sci-fi/fantasy franchise in Avatar, and loaded up on popular television fare including The Simpsons and American Horror Story. It plans to harness this wealth of entertainment assets to launch a streaming service of its own to challenge Netflix.

The mega-merger only underscores the fate of the media left-behinds, those smaller industry players that will find it increasingly hard to survive in the land of giants.

Veteran telecommunications industry analyst Craig Moffett has been tracking, quarter by quarter, the steady loss of cable and satellite TV subscribers and the gains made by new distributors like SlingTV, DirecTV Now, Hulu TV, Sony PlayStation Vue and YouTube TV.

Moffatt notes that the number of subscribers to these new, cheaper digital alternatives, or virtual MVPDs, is hard to quantify — the best guess is around 3.4 million subscribers to date.

But the winners and losers are starkly apparent. Traditional broadcasters — ABC, CBS, NBC and Fox — are included in these new, cheaper programming bundles. Players with cable-only offerings, like Viacom or Discovery Networks, have “huge holes in their coverage.”

“This yawning disparity with respect to positioning among vMPDs is unmistakable in the numbers,” Moffett observed, adding that, “In a rapidly shrinking distribution universe, inclusion on the emerging alternatives is seen as an imperative.”

This harsh reality may drive weaker television players, like Viacom, into the hands of an acquirer — or perhaps renew conversations to reconcile with its network ex, CBS. While it has recovered from the chaos and ratings free-fall of the late-Philippe Dauman period, Viacom under CEO Bob Bakish has a potent set of cable assets but also a host of questions around advertising revenue and the turnaround prospects for Paramount Pictures.

Lionsgate has been a consistent acquirer of companies, absorbing Starz this year after a previous deal for Summit. It also is among the bidders on the distressed, though still valuable, remnants of The Weinstein Company. But Lionsgate’s collection of media properties also could make it an attractive acquisition target — especially for a company shopping for content.

The Santa Monica entertainment company’s television business encompasses nearly 90 shows on 40 different networks, including Netflix hit Orange is the New Black and syndicated juggernaut Family Feud. Its feature film unit, even without more installments in the Hunger Games young adult franchise, outperformed one of the six major studios (Paramount) at the domestic box office in 2017. The company has scored this year with family film Wonder and carryover business from Oscar-nominated musical La La Land. In October, it announced Joe Drake was returning to the company as co-chair of the film unit.

Direct-to-consumer is another key priority for Lionsgate, which added two new streaming services to Starz’s 2-million-subscriber-strong on-demand platform. Two more streaming services launched over the summer — Kevin Hart’s Laugh Out Loud and Pantaya, which offers day-and-date access to Spanish-language films as they debut in Latin American theaters.

Regulatory changes in Washington, D.C., may well accelerate the pace of media acquisitions.

The FCC’s vote to repeal net neutrality rules clears the way for telecommunications companies and cable operators to prioritize access to their networks — essentially, collecting a toll from streaming services looking to deliver content to subscribers.

“Which could mean that any digital service will only be able to guarantee their U.S. users a high quality of service if they broker a deal with each and every telco,” wrote Midia analyst Mark Mulligan.

Telecommunications companies may well abandon all pretense to “neutrality,” and give an edge to entertainment services they own. Sprint might decide to make song streaming flawless when delivered via its part-owned music service, Tidal, but less musical for Spotify or Apple Music. Similarly, AT&T could throttle video viewing on Netflix to give an advantage to its own DirecTV Now service.

“Those telcos without strong content plays could find themselves in the market for acquisitions,” Mulligan writes. “For example, Verizon could make a bid for Spotify.”

As the FCC throws out the rulebook on the Internet, it is making similar moves to strip away decades of regulation limiting local TV ownership. As Sinclair gets set to claim TV stations that could reach a majority of U.S. households (far more than the previous 39% cap imposed by the FCC), Fox is also salivating at the thought of ramping up in local. Meredith, having swallowed up debt-laden Time Inc. this year, may be less inclined to hang onto its station portfolio, some Wall Streeters reckon.

With its asynchronous moves in 2017, the Department of Justice, which filed suit to block AT&T-Time Warner, will be a major factor in 2018 on the deal front, as will the FCC.

With its asynchronous moves in 2017, the Department of Justice, which filed suit to block AT&T-Time Warner, will be a major factor in 2018 on the deal front, as will the FCC.

Doug Creutz, an analyst with Cowen, issued a note just before Christmas raising his price target on Disney and predicting a final blessing by the DoJ. “In most of the main areas where the DoJ could have an objection — consolidation of TV studios, ownership of the regional sports networks, taking control of Hulu — we think Disney has a fairly compelling pro-consumer argument to make,” he wrote, compared to the comparatively “vague” assertions of AT&T.

In one alarm bell that Hollywood should heed, he added that the merger of the two film studios could be what gets tripped up by regulators given that Disney and Fox could control more than one-third of domestic grosses in a typical year.

With Pixar, Marvel and Lucasfilm already delivering best-in-class results, Disney would likely agree with leaving the Fox studio behind or allowing another buyer to snatch it up, he wrote. “The film studio is far less crucial to Disney’s OTT plans and doesn’t offer them much that they don’t already do better.”